Resilient Distributed Datasets A Fault-Tolerant Abstraction for In-Memory Cluster

Abstract

- RDD

- Resilient Distributed Datasets

- in a

fault-tolerant manner - in-memory computations

on large clusters

- in a

- Resilient Distributed Datasets

- RDDs are motivated by

- iterative algorithms

- interactive data mining tools

keeping data in memory can improve performance by an order of magnitude

1. Introduction

- Current frameworks provide numerous abstractions for accessing a cluster’s computational resources, they lack abstractions for leveraging distributed memory

- This makes them

inefficientfor an important class of emerging applications- reuse

intermediateresults across multiple computations interactivedata mining, where a user runs multiple adhoc queries on the same subset of the data

- reuse

- RDD enables efficient data reuse in a broad range of applications

fault-tolerantparallel data structuresthat let users explicitly persist intermediate results in memory, control their partitioning to optimize data placement, and manipulate them using a rich set of operators

- Existing abstractions for in-memory storage on clusters, such as distributed shared memory, keyvalue

stores, databases, and Piccolo, offer an

interface based on fine-grained updates to mutable state

(cells in a table)

- With this interface, the only ways to provide fault tolerance are to replicate the data across machines or to log updates across machines

- Both approaches are expensive for data-intensive workloads

- RDDs provide an interface based on coarse-grained transformations (map, filter and join) that apply the same operation to many data items

- This allows them to efficiently provide

fault tolerance by logging the transformationsused to build a dataset (its lineage) rather than the actual data

- This allows them to efficiently provide

- We have implemented RDDs in a system called Spark

- Spark is up to 20× faster than Hadoop for iterative applications

2. Resilient Distributed Datasets (RDDs)

- define RDDs

- introduce their programming interface in Spark

- compare RDDs with fine-grained shared memory abstractions

- discuss limitations of the RDD model

2.1 RDD Abstraction

- RDD is a

read-only,partitioned collection of records - RDDs can

only be createdthrough deterministic operations on either data in stable storage or other RDDs - We call these operations

transformations- transformations include map, filter, and join

- RDDs do not need to be materialized at all times

- RDD has enough information about how it was derived from other datasets (its lineage) to compute its

partitions from data in stable storage

- program cannot reference an RDD that it cannot reconstruct after a failure

- users can control two other aspects of RDDs:

persistenceandpartitioning- Users can indicate which RDDs they will reuse and choose a storage strategy for them

- They can also ask that an RDD’s elements be partitioned across machines based on a key in each record

- This is useful for placement optimizations, such as ensuring that two datasets that will be joined together are hash-partitioned in the same way

2.2 Spark Programming Interface

- Programmers start by defining one or more RDDs through transformations on data in stable storage

- Programmers can then use these RDDs in

actions, which are operations that return a value to the application or export data to a storage system - Programmers can call a

persistmethod to indicate which RDDs they want to reuse in future operations- Spark keeps persistent RDDs in memory by default,

but

it can spill them to disk if there is not enough RAM - Users can also request other persistence strategies, such as storing the RDD only on disk or replicating it across machines, through flags to persist

- Users can set a persistence priority on each RDD to specify which in-memory data should spill to disk first

- Spark keeps persistent RDDs in memory by default,

but

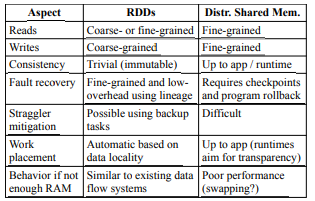

2.3 Advantages of the RDD Model

- In DSM(distributed shared memory) systems, applications read and write to arbitrary locations in a global address space

- DSM is a very general abstraction, but this generality makes it harder to implement in an efficient and fault=tolerant manner on commodity clusters

- The main difference between RDDs and DSM

- RDDs can only be created through coarse-grained transformations

- DSM allows reads and writes to each memory location

- This restricts RDDs to applications that perform bulk writes, but allows for more efficient fault tolerance

- RDDs do not need to incur the overhead of check pointing, as they can be recovered using lineage

- only the lost partitions of an RDD need to be recomputed upon failure, and they can be recomputed in parallel on different nodes, without having to roll back the whole program

- immutable nature lets a system mitigate slow nodes (stragglers) by running backup copies of slow tasks as in MapReduce

- in bulk operations on RDDs, a runtime can schedule tasks based on

data locality to improve performance RDDs degrade gracefully when there is not enough memory to store them, as long as they are only being used in scan-based operations- Partitions that do not fit in RAM can be stored on disk and will provide similar performance to current data-parallel systems

2.4 Applications Not Suitable for RDDs

- RDDs are best suited for batch applications that apply the same operation to all elements of a dataset

- RDDs can efficiently remember each transformation as one step in a lineage graph and can recover lost partitions without having to log large amounts of data

- RDDs would be less suitable for applications that make asynchronous fine-grained updates to shared state, such as a storage system for a web application or an incremental web crawler

- it is more efficient to use systems that perform traditional update logging and data checkpointing, such as databases

- Our goal is to provide an efficient programming model for batch analytics and leave these asynchronous applications to specialized systems

3. Spark Programming Interface

- We chose Scala due to its combination of conciseness (which is convenient for interactive use) and efficiency (due to static typing)

- nothing about the RDD abstraction requires a functional language

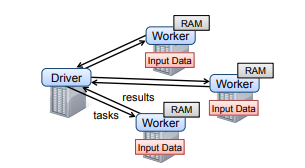

- To use Spark, developers write a

driverprogram that connects to a cluster of workers

- The driver defines one or more RDDs and invokes actions on them. Spark code on the driver also tracks the RDDs’

lineage - The workers are long-lived processes that can store RDD partitions in RAM across operations

- Scala represents each closure as a Java object, and these objects can be

serializedandloaded on another nodeto pass the closureacross the network

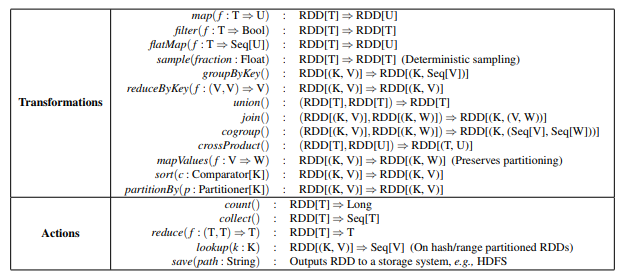

3.1 RDD Operations in Spark

transformations are lazy operationsthat define a new RDD, whileactions launch a computation to return a valueto the program or write data to external storage- some operations, such as join, are only available on RDDs of key-value pairs

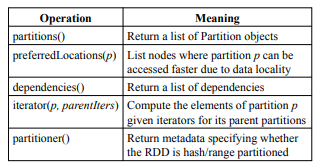

4. Representing RDDs

- A system implementing RDDs should provide as rich a set of transformation operators as possible

- let users compose them(operators) in arbitrary ways

- We propose a

simple graph-based representationfor RDDs that facilitates these goals- used this representation to support a wide range of transformations without adding special logic to the scheduler for each one, which greatly simplified the system design

- representing each RDD through a common interface that exposes five pieces of information

- a set of

partitions- atomic pieces of the dataset

- a set of

dependencieson parent RDDs- a function for computing the dataset based on its parents

- metadata about its partitioning scheme and data placement

- a set of

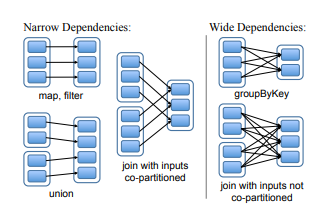

- how to represent dependencies between RDDs

narrow dependencies- where each partition of the parent RDD is used by at most one partition of the child RDD

mapleads to a narrow dependency

wide dependencies- where multiple child partitions may depend on it

joinleads to to wide dependencies

- This distinction(narrow, wide) is useful for two reasons

- narrow dependencies allow for

pipelined execution on one cluster node - wide dependencies require data from all parent partitions to be available and to be shuffled across the nodes using a MapReducelike operation

- recovery after a node failure is more efficient with a narrow dependency, as only the lost parent partitions need to be recomputed, and they can be recomputed in parallel on different nodes

- in a lineage graph with wide dependencies, a single failed node might cause the loss of some partition from all the ancestors of an RDD, requiring a complete re-execution

- narrow dependencies allow for

5. Implementation

- Spark in about 14,000 lines of Scala

- The system runs over the

Mesoscluster manager allowing it to share resources with Hadoop - sketch several of the technically interesting parts of the system

- job scheduler

- Spark interpreter allowing interactive use

- memory management

- support for checkpointing

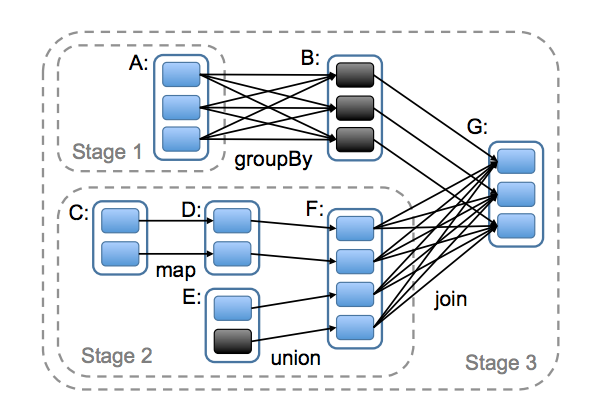

5.1 Job Scheduling

- Spark’s scheduler uses representation of RDDs, described in Section 4

- Scheduler is similar to Dryad’s, but it additionally takes into account which partitions of persistent RDDs are available in memory

- Whenever a user runs an action (count, save..) on an RDD, the scheduler examines that RDD’s lineage graph to build a DAG of stages to execute

- Each stage contains as many pipelined transformations with narrow dependencies as possible

- The boundaries of the stages are the shuffle operations required for wide dependencies, or any already computed partitions that can shortcircuit the computation of a parent RDD

- The scheduler then launches tasks to compute missing partitions from each stage until it has computed the target RDD

- Scheduler assigns tasks to machines based on data locality using delay scheduling

- If a task needs to process a partition that is available in memory on a node, we send it to that node

- If a task processes a partition for which the containing RDD provides preferred locations, we send it to those

- For wide dependencies(shuffle dependencies), we currently materialize intermediate records on the nodes holding parent partitions to simplify fault recovery, much like MapReduce materializes map outputs

- If a task fails, we re-run it on another node as long as its stage’s parents are still available

- If some stages have become unavailable, we resubmit tasks to compute the missing partitions in parallel

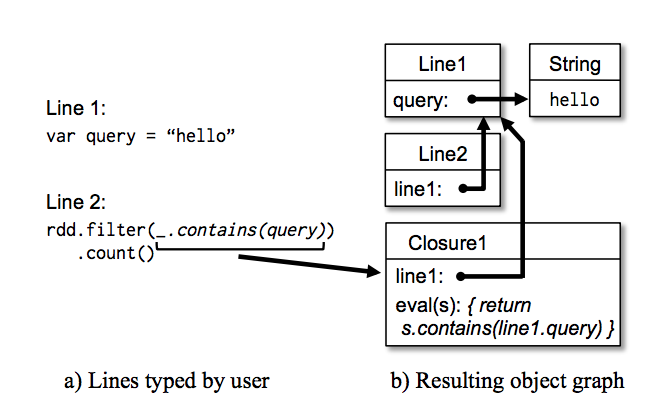

5.2 Interpreter Integration

- Scala includes an interactive shell similar

- Scala interpreter normally operates by compiling a class for each line typed by the user, loading it into the JVM, and invoking a function on it

- If the user types

var x = 5followed by println(x), the interpreter defines a class called Line1 containing x and causes the second line to compile toprintln(Line1.getInstance().x)

- Given the low latencies attained with in-memory data, we wanted to let users run Spark interactively from the interpreter to query big datasets

- two changes to the interpreter in Spark

Class shipping- To let the worker nodes fetch the bytecode for the classes created on each line,

we made the interpreter serve these classes over HTTP

- To let the worker nodes fetch the bytecode for the classes created on each line,

Modified code generation- we serialize a closure referencing a variable defined on a previous line, such as

Line1.xin the example above, Java will not trace through the object graph to ship the Line1 instance wrapping around x. Therefore, the worker nodes will not receivex - We modified the code generation logic to reference the instance of each line object directly

- we serialize a closure referencing a variable defined on a previous line, such as

5.3 Memory Management

- Spark provides three options for storage of persistent RDDs

- in-memory storage as deserialized Java objects

- fastest performance

- The Java VM can access each RDD element natively

- in-memory storage as serialized data

- lets users choose a more memory-efficient representation than Java object graphs when space is limited, at the cost of lower performance

- on-disk storage

- useful for RDDs that are too large to keep in RAM but costly to recompute on each use

- in-memory storage as deserialized Java objects

- To manage the limited memory available, we use an

LRU eviction policyat the level of RDDs- When a new RDD partition is computed but there is not enough space

to store it, we evict a partition from

the least recently accessed RDD,unless this is the same RDDas the one with the new partition - we keep the old partition in memory to prevent cycling partitions

from the same RDDin and out - This is important because most operations will run tasks over an entire RDD, so it is quite likely that the partition already in memory will be needed in the future

- When a new RDD partition is computed but there is not enough space

to store it, we evict a partition from

5.4 Support for Checkpointing

- Although lineage can always be used to recover RDDs after a failure, such recovery may be

time-consuming for RDDs with long lineage chains - It can be helpful to

checkpointsome RDDs to stable storage. checkpointingis useful for RDDs with long lineage graphs containing wide dependencies- Spark currently provides an API for checkpointing (a

REPLICATEflag to persist), but leaves the decision of which data to checkpoint to the user

참고

- https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/nsdi12/nsdi12-final138.pdf

Published 25 September 2018